A Problem About Values

-

Larry Blomme

Larry Blomme - 04 Feb, 2025

What is it to value something? What is value? These are not the nebulous and maybe useless questions that we might think they are. Only if we know what value is can we aim at it. We can take steps to improve our lives, to fill them with value. As philosophers, we can even hope to explain why we value things, instead of just taking it for granted that we do. You might be surprised to know that I am not the first person to ask these questions. In fact, many people have had thoughts on the matter, and these thoughts have tended to condense into two particular kinds of view. The first is that whatever it is we value - whatever there is that is valuable - can be explained in one way or another as a single thing. The other argues that we value many distinct and irreducible things. Before going further, I will outline these positions.

Value Monism

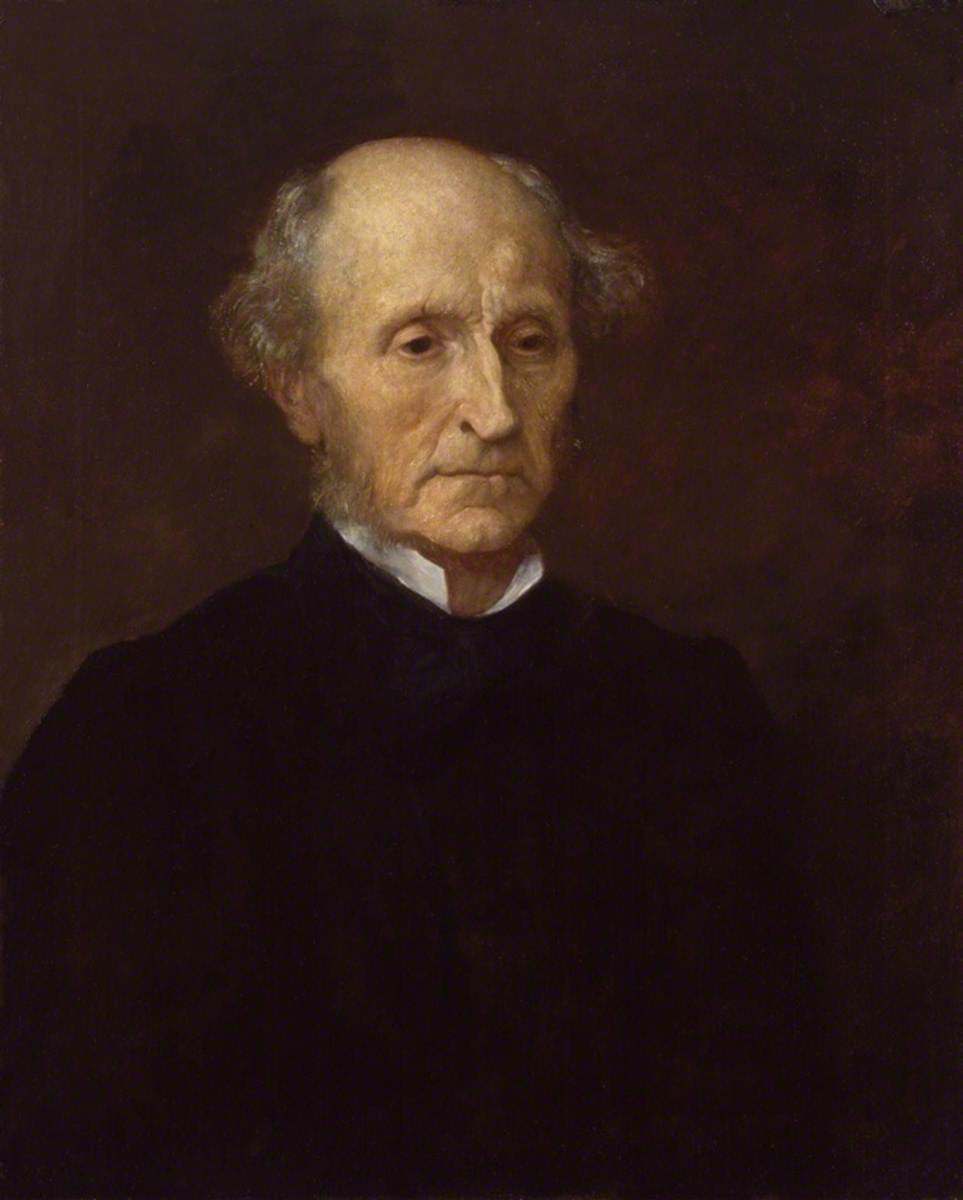

The idea that we value one basic or fundamental thing in every other valuable thing can be traced back a very long way. The Greek philosopher Epicurus was one of the ancient philosophers who taught that only pleasure (and the absence of pain) is good, while only pain is bad. This view, commonly called hedonism, has long taught that whatever we value is valuable because it promotes pleasure. Other philosophers that might be a worthwhile research session include Jeremy Bentham and J.S. Mill - both arguing that pleasure is the ultimate, fundamental good. Hedonism is one kind of value monism, which is just any theory that holds that only one fundamental value exists. While it’s the most popular, there are other options. One of those options is Moorean monism - which comes from the philosopher G.E. Moore and holds that goodness is the single fundamental property that all good things instantiate.

Value monism is a tempting view. After all, it seems to be true! When we say that we like tasty tacos, we say it’s because “they’re so good!” Why are they good, though? That’s where we have to draw the line - they’re either good because they’re so tasty (i.e. the tastiness makes them good, which is just a restatement) or they’re just good, darn it! Mill or Bentham would say that they’re good because it feels good to eat them; they generate pleasure. Either way, we have a simple explanation that gives everything good, for any reason, a common ancestry. Moral goodness, aesthetic goodness, the goodness of wisdom and knowledge, all of these are good because they instantiate or possess one property. This lets us weigh difficult decisions in a rational way - just figure out how much goodness your choices will generate, and pick the one that will make the most good a reality. But then what exactly makes different values different? Why do we have different names for different kinds of goodness? And if we think knowledge is good (or pleasurable) it’s certainly a different kind of goodness (or pleasure) than tasty tacos or moral goodness!

Value Pluralism

This is where the value pluralists come in. They argue that there is more to the story than just one simple fundamental value. Instead, there are potentially a great many fundamental values - knowledge, wisdom, pleasure, moral goodness. All of these are irreducible to any other, and there is, as a result, no way to compare between them. Instead of moral goodness being better than pleasure, it’s just different. This explanatory move has the benefit of explaining why we seem to recognize so many different values around us. It also explains why we find it so hard to compare between things that we find fundamentally valuable. Unfortunately, this strength is also a weakness. Since we can’t ever rationally compare between values, there is no way to make decisions where one must be weighed against another. For example, if you have to decide between doing the right thing or feeling good (given that doing the right thing won’t make you feel even better!) then you have to just guess. There is no rational way to argue that one is better than the other. This is also a problem for politics: if we have to decide between benefitting our citizens or the environment, it seems we have to pick between two incommensurate values. Value pluralists have no rational way to do this.

Saving the Day

Value pluralists and monists each face problems - it seems obvious that there is more to what we value than just a quantity of some single thing like pleasure. Even so, we want to be able to say why some values are better than others. The problem for pluralists is that this is absolutely impossible. If each value is equally fundamental and unique, and completely irreducible, there will never be a way to say that one is absolutely better or more important than another.

The Pluralist Move

Some pluralists have argued that values can be compared, but not with more fundamental values. Instead, less fundamental values in certain contexts can be used as the comparison. It’s best to use an example. Say you’re trying to decide whether to hire a conductor for your orchestra. You have two choices: a creative genius with a poor grasp of the construction methods of string instruments, or a rather dull, skilled conductor who knows the ins and outs of making string instruments as well as the history of music. Given that both possess the skill of conducting, do you value creativity or knowledge more? In this case, since you are looking for a conductor, you decide that creativity is more important and hire the creative genius. The way you compare the two is not by reference to some deeper value, in this case, but rather a shallower one. The shallower value is the value of being a good conductor for your orchestra, one that is made up of skill, creativity, and many other more fundamental values that you look for in your hiring process.

This is odd! Saying that creativity is better than knowledge in this case is reliant on you and your context, which does not allow us to compare the values at all. Rather, we compare their usefulness to us in certain situations, where of course one or another can come out on top. This complicates things: the usefulness of a value in a situation is taken as valuable! Why is it that the value of usefulness is the one we’ve decided to use as our measure? Is it just because we need to get things done? If that’s the case, then we aren’t comparing values at all, we’re just saying that one value is better than another in our case because it’s more useful. If it’s not just because we need to get things done, we run the risk of making usefulness our ultimate, supreme value, by which all others are compared. This has been done, but it’s not value pluralism; it’s more akin to pragmatism. It is not clear that this method saves the pluralist from the sorts of problems that I’ve described.

The Monist Move

Value monists have their own move to save the view from accusations that value, as a single thing that can only be quantified, is just too shallow to describe what we know value to be. Monists argue that their single value has more than one quality, too. This is popularly credited to J.S. Mill, who held that in addition to more or less pleasure, there are also different kinds of pleasure. Mill thought that intellectual pleasures were better than base, physical pleasures, meaning that we can compare a lot of physical pleasure to some smaller amount of intellectual pleasure and they would have the same overall value. The details of this view aren’t quite worked out by any monist, I think because the details involve some sort of equation and giving a function for value qualities to quantities would be both highly difficult and highly contentious.

The monists who argue for both quality and quantity of value face the accusation of just being pluralists in disguise. If intellectual pleasure, for example, is just different from physical pleasure, how can we say that these both are parts of the same fundamental value? If they really are entirely different qualitatively, what do they hold in common? We can’t say for pleasure that it’s the feeling, because the feeling itself is supposed to be of a totally different quality if we take the route that Mill did.

What’s Left?

As I’ve described it, pluralism seems to save itself by turning to usefulness or some similar value as more fundamental, thus looking like a monist theory in disguise. Monism, though, saves itself by a move that makes it look pluralist! If this entire debate comes down to ‘meeting in the middle’, we can handle that. After all, what each theory tells us to do in particular cases might very well be the same. The difference might just hide in the way that we frame the problem. But this isn’t good enough - each theory does not work on its own terms as I’ve laid it out. The pluralists aren’t pluralist enough, and the monists aren’t monist enough. What we need is an alternative that gives us the theoretical and practical benefits of both, but does not have to shy away from the very intuitions that give it reason to exist. The ‘middle’ in which we meet should not be an ambiguity between two opponents. It should be an idea of value that is clearly laid out.

The Alternative

Thinking of the theoretical playing field somewhat schematically, we have discussed pluralism in two varieties, and both seem to succumb to the incomparability problem or else turn into monism. Monism, likewise, we have discussed as both quantifiable and qualifiable+quantifiable. Monism has a third potential option which we did not discuss - a single qualifiable, but not quantifiable, fundamental value. I do not know why this has not always been an option, but I wish to argue that it is worth considering.

Before I do that, I will describe more precisely what I mean. I will use ‘goodness’ in the Moorean sense, as the fundamental monist value. On my unidimensional quality account of monism, there is only goodness as the fundamental value. All other things are valuable to the extent to which they are good. Goodness is not something that we can quantify here, instead only having qualities like moral goodness, Meaning something good you experience, like pleasure phenomenal goodness, epistemological goodness, etc. Some of these qualities may be more good than others. Perhaps we can argue that moral goodness is always better than phenomenal goodness, and should always be preferred.

But wait - how can I say that moral goodness is more good if goodness itself cannot be measured? I certainly cannot say that moral goodness contains more goodness! Instead, I must say that moral goodness is more like goodness itself, while phenomenal goodness is less like goodness. In this way, we can describe what makes us prefer some goods to others in a rational way. Because of this, we can make rational decisions about competing goods in a relatively straightforward manner. Not only this, but we escape the pluralist claim that we are secretly pluralists! Since we have a fundamental value, our derivative values need not suffer from the accusation that they are fundamental and can even be measured quantitatively. So we can say one option causes more pleasure than another, or is morally better than another, without contradicting our thesis that goodness itself cannot be measured. When we are faced with the choice between a great deal of pleasure or a little moral goodness, we can decide by prioritizing the higher good. This is a result that many should find intuitive.

This alternative, which we can call the quality account of the good, seems to check all of our boxes without being inconsistent. It is monist and sticks to its claim of monism, but allows for different kinds of non-fundamental values. This explains the pluralists’ intuition that there are qualitatively different kinds of value that cannot be reduced to each other. On my quality account, moral goodness might be reduced to goodness itself, but it is not reducible to any other value like pleasure. My account can also allow us to easily ‘rank’ non-fundamental values, because they all are like the good, but not to the same extent.

This post is a continuation of a presentation I gave on Christian Blum’s Value Pluralism Versus Value Monism, published in Acta Analytica 38 (2023) 627–652.